As rhythm and blues gained popularity among teenagers in the early 1950s, songs by artists like Little Richard and Fats Domino captivated young listeners with their energetic delivery and suggestive lyrics. Tracks such as Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” with its playful line, “I got a girl named Sue, she knows just what to do,” and Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle, and Roll,” featuring the lyric, “You’re wearin’ those dresses, the sun comes shinin’ through / I can’t believe my eyes, all of this belongs to you,” represented a bold and vibrant style that resonated with youth culture. While many of these artists had crossover success with young white listeners these same qualities alarmed many parents, broadcasters, and record executives, who viewed the content as too risqué for mainstream white audiences.

In response, white artists and record labels began releasing cover versions of rhythm and blues songs originally performed by Black musicians. Although a cover version typically refers to any re-recording of an existing song, in this context, these renditions served a more deliberate function: to repackage Black musical innovations in a form deemed more appropriate and commercially viable for white listeners.

Original recordings often featured sexually suggestive lyrics delivered with humor, double meanings, and emotional intensity—hallmarks of the rhythm and blues tradition. Many record executives, however, regarded these lyrical elements as inappropriate and potentially offensive. In cover versions, lyrics were frequently altered or sanitized, and performance styles were softened to remove the perceived edginess of the originals. Pat Boone became the most prominent figure associated with this trend. His versions of “Ain’t That a Shame,” “Long Tall Sally,” and “Tutti Frutti” stripped away the raw vocal power and sexual innuendo of the original recordings, replacing them with smooth, restrained performances that appealed to white middle-class audiences and radio stations.

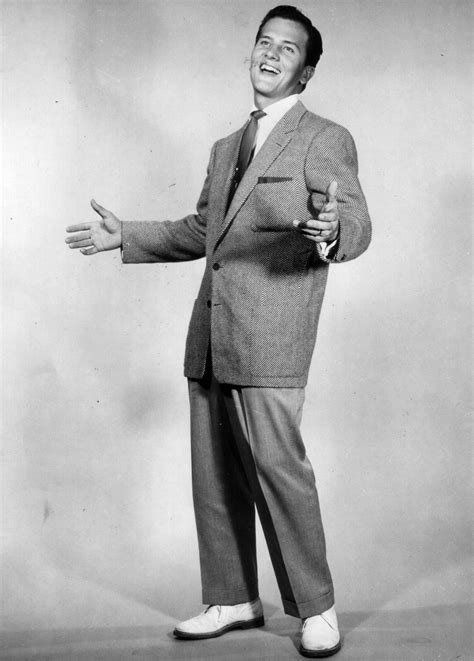

Pat Boone (b. 1934) emerged as one of the most commercially successful artists of the 1950s, second only to Elvis Presley in terms of chart dominance. Over the course of the decade, Boone sold nearly 50 million records and charted 38 Top 40 hits. His popularity was largely built on polished toned-down versions of rhythm and blues songs originally written and performed by Black artists. These renditions were carefully crafted to appeal to white, middle-class audiences who might have found the original versions too raw, intense, or sexually suggestive.

Boone’s approach exemplified a broader trend in American popular music during the early rock and roll era: the repackaging of Black musical innovation into a more “acceptable” form for mainstream white consumers. His early hits included sanitized covers of “Ain’t That a Shame” by Fats Domino and “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally” by Little Richard. While Boone's interpretations lacked the rhythmic intensity and vocal grit of the originals, they introduced these compositions to audiences and radio stations that were otherwise hesitant—or outright unwilling—to feature recordings by Black musicians. Boone himself acknowledged the racial and cultural implications of his early career. “I like to say I was the midwife at the birth of rock and roll,” he once remarked. “In fact, there was no such thing as rock and roll. It was called ‘race music,’ and the artists were limited to their own stations and charts.” While his statement recognizes the Black origins of the genre, it also highlights the systemic barriers that limited access to broader markets for many Black performers. Boone’s commercial success often came at their expense: original artists received little recognition or compensation while his covers reached mass audiences and earned significant profits

Stylistically, Boone embodied a softer, more conservative vision of 1950s popular music. His clean-cut image, wholesome persona, and relaxed vocal delivery provided an alternative to the rebellious energy of performers like Elvis Presley, Little Richard, or Chuck Berry. His musical output ranged from upbeat tunes like “Why Baby Why” and “Wonderful Time Up There” to romantic ballads such as “Love Letters in the Sand,” “April Love,” and “Sugar Moon.” While many of his recordings clearly fall within the pop tradition of Tin Pan Alley and Hollywood studio music, others—such as his television performances of “Tutti Frutti”—display basic rock and roll elements, even if presented in a much more restrained style.

Boone's critics have long argued that his career exemplifies cultural appropriation, capitalizing on the artistic labor of Black musicians while benefiting from racial privilege in a segregated music industry. While there is truth to this critique, it is also historically accurate to note that Boone’s recordings helped bring rhythm and blues compositions into broader circulation at a time when systemic racism severely limited the reach of Black performers. In this way, Boone’s legacy is complex: he was a key figure in the popularization of rock and roll, but his success also reflects the racial inequalities embedded in the music industry of the era.

By repackaging the sounds of rhythm and blues into a form palatable to mainstream America, Boone played a central role in shaping early rock and roll’s commercial trajectory. His career helps illuminate how issues of race, representation, and cultural ownership were—and continue to be—deeply woven into the fabric of American popular music.