In postwar Britain, the late 1950s and early 1960s witnessed the rise of two competing youth subcultures: the Rockers and the Mods. These groups emerged from different social and cultural milieus, yet both responded to a rapidly changing society marked by postwar affluence, consumerism, and the growing visibility of youth as a distinct cultural force.

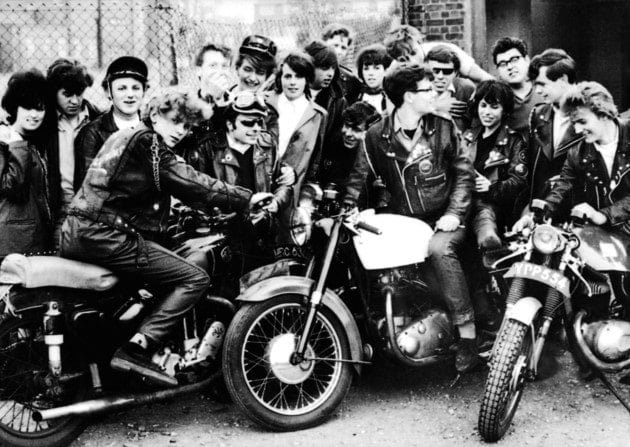

The Rockers, sometimes called ton-up boys or leather boys, were closely associated with motorcycle culture and 1950s American rock and roll. Their identity revolved around speed, rebellion, and a rugged form of masculinity. They rode British motorbikes like Triumphs and BSAs, aiming to hit "the ton" (100 mph), a rite of passage in the rocker scene. Their look, heavily influenced by films like The Wild One (1953) starring Marlon Brando, included black leather jackets, denim, chain wallets, and greased-back pompadours. Their music tastes gravitated toward early rockers such as Elvis Presley, Eddie Cochran, and Chuck Berry. Rockers projected an image of cultural defiance and a shared sense of outsider identity, one that was eagerly sensationalized by the British press.

In contrast, the Mods represented a more fashion-forward, urbane, and style-conscious youth movement. Short for "Modernists," the term originally referred to fans of modern jazz, but by the early 1960s it had evolved into a full-fledged subculture centered in London. Mods rejected the leather-clad aesthetic of the Rockers and instead favored tailored Italian suits, narrow ties, button-down shirts, desert boots, and military-style parkas. These were practical for riding their preferred mode of transportation, the Vespa or Lambretta scooter, often decorated with a multitude of rearview mirrors and lights. Their musical tastes were more cosmopolitan, drawing from American soul, Motown, jazz, and R&B, as well as contemporary British beat groups. Coffee bars, unlike pubs, were central social hubs for Mods, offering late-night music, amphetamines, and a space where working-class and middle-class youth could mix freely.

The cultural divide between Mods and Rockers reached a breaking point in the spring and summer of 1964, when a series of violent clashes erupted in British seaside towns such as Brighton, Margate, and Clacton-on-Sea. These confrontations, which were largely exaggerated in scale by the British tabloid press, ignited a moral panic. Headlines warned of a youth culture run amok, while politicians and moralists decried the breakdown of British decency. In retrospect, many sociologists and historians view the panic as emblematic of broader anxieties about class, authority, and generational change in 1960s Britain.

Although the clashes began to subside by 1965, the Mod and Rocker rivalry became embedded in British popular memory. The Mod subculture, in particular, evolved rapidly. It expanded from its working-class jazz and soul roots to become a broader signifier of youth style and experimentation. London became the epicenter of this transformation, especially in neighborhoods like Carnaby Street and Soho, where boutique fashion, live music clubs, and art movements like Pop Art converged to define the era of Swinging London. Models like Twiggy and bands like The Small Faces and The Kinks became Mod icons, and the style began to be exported internationally, influencing American fashion and music scenes by the mid-1960s.

Amid the cultural ferment of early 1960s Britain, The Who emerged as a band uniquely suited to capture the spirit—and contradictions—of the Mod movement. With their sharp fashion sense and R&B-inflected sound, they became one of the definitive Mod bands. Yet their raw power, aggressive performances, and notorious habit of destroying instruments onstage also echoed the intensity and volatility often associated with Rocker culture. In this way, The Who straddled both worlds, bridging the tailored refinement of Mod style with the reckless fury of rock rebellion. They came to embody the musical experimentation and generational defiance that fueled Britain’s youth explosion.

Formed in London in the early 1960s, the band began as The Detours before briefly adopting the name The High Numbers to appeal to a Mod audience. Eventually, they changed their name to The Who and solidified their classic lineup: Pete Townshend on guitar, John Entwistle on bass, Roger Daltrey on vocals, and Keith Moon on drums. Each member projected a distinct persona onstage. Pete Townshend, the band's primary songwriter, brought a sharp, intellectual edge to The Who’s music. His lyrics often explored themes of alienation, identity, and rebellion, reflecting his interest in literature and philosophy. Onstage, he introduced the now-famous "windmill" technique, swinging his arm in a circular motion to strike the guitar strings with force—a move that became one of rock’s most iconic visual trademarks. Roger Daltrey added a commanding presence as lead vocalist, often described as prowling the stage with the intensity of a lion. John Entwistle, known as "The Ox," anchored the band with a stoic demeanor and virtuosic bass playing, his melodic lines frequently carrying as much weight as the guitar. Behind the drums, Keith Moon generated a sense of barely contained chaos. His playing was frenetic and unpredictable, yet always in conversation with the music. Together, their contrasting styles and distinct personalities created a powerful dynamic that set The Who apart from their peers.

The Who distinguished themselves musically through a blend of sonic innovation and intensity. With only one guitarist in the band, Pete Townshend developed a hybrid style that moved seamlessly between rhythm and lead. He favored powerful chords over traditional solos, using feedback, distortion, and dynamic shifts to transform the guitar into an expressive and sometimes destructive instrument. Keith Moon’s drumming filled the space left by the absence of a second guitarist. His playing was energetic and explosive, providing a wild contrast to John Entwistle’s intricately melodic bass lines. Together, Moon and Entwistle expanded the band’s sonic range and helped establish the power trio format that would later inspire groups like Cream, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, and The Jam.

The Who’s fashion also reflected their connection to Mod culture. Early on, they wore sharp suits, Union Jack jackets, polka dots, and military-style coats. Townshend’s preference for boiler suits and Moon’s playful, often bold outfits highlighted their distinct personalities. Their style combined clean-cut looks with a rebellious edge, rooted in Mod ideals but always pushing boundaries. In an era where image mattered almost as much as sound, The Who delivered both.

The Who’s rise to prominence began with the 1965 single “My Generation,” which became a defining anthem for the Mod movement and the rebellious spirit of British youth. The song’s sharp melody and aggressive energy set it apart, while its most famous line—“Hope I die before I get old”—expressed a raw defiance that resonated deeply with a disaffected generation. Lead singer Roger Daltrey’s vocal delivery featured a distinctive stutter, adding urgency and frustration to the lyrics. This stuttering style may have been inspired by blues musician John Lee Hooker’s “Stuttering Blues” or suggested to mimic the effects of amphetamines used by Mods. Regardless of its origin, the stutter became an iconic part of the song’s identity.

Musically, “My Generation” draws heavily from American rhythm and blues, particularly through its call-and-response structure. Daltrey sings a line, followed by backing vocals from Pete Townshend and John Entwistle echoing the refrain “Talkin’ ’bout my generation.” The instrumental section mirrors this interaction, with solos passing back and forth between Townshend’s guitar and Entwistle’s bass. Notably, the song includes one of rock’s earliest bass solos, performed by Entwistle on his Fender Jazz Bass. Keith Moon’s drumming adds a frenetic pulse, driving the song forward with explosive energy. The track ends not with a clean finish but a chaotic coda of feedback and noise, underscoring the band’s willingness to push sonic boundaries.

Their live shows gained a reputation for their intense destruction. An accidental moment, when Townshend struck his guitar against a low ceiling, soon became a purposeful act incorporated into their shows. Moon followed by breaking his drum kit, and the band made this destructive finale a signature part of their performances.

One of The Who’s most memorable moments occurred in 1967 during their appearance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. At the end of the performance, Pete Townshend began to smash his guitars and destroy amplifiers while Roger Daltrey energetically slung his microphone around the stage. Keith Moon set off explosives in his bass drum, creating a dramatic blast that stunned the audience, singed Townshend’s hair, and reportedly contributed to his partial hearing loss in one of his ears. This event became emblematic of the band’s volatile mix of spectacle and danger.

While The Who had already gained success in Britain, their breakthrough in the United States came later that year with a powerful set at the Monterey Pop Festival. They followed this with the release of the psychedelic single “I Can See for Miles,” which marked their first major U.S. chart success. Their 1967 album, The Who Sell Out, cleverly parodied British pirate radio through fake commercials and jingles, ending with the ambitious mini-opera “Rael.” These theatrical ideas reached their peak in 1969 with Tommy, a rock opera telling the surreal story of a “deaf, dumb, and blind” pinball prodigy. Tommy demonstrated that rock music could be conceptually and narratively complex.

By combining raw energy, musical innovation, and dramatic ambition, The Who redefined rock music. They delivered more than sound—they created a full experience. In doing so, they laid the foundation for countless bands to follow, proving that rock could be explosive, stylish, thoughtful, and unapologetically loud.