The Beatles’ story began on a summer afternoon in 1957, when sixteen-year-old John Lennon met fifteen-year-old Paul McCartney at a church party in the Liverpool suburb of Woolton. Lennon was fronting his skiffle group, the Quarrymen, hammering out rough-hewn versions of American rock and roll standards. McCartney, recently introduced by a mutual friend, impressed Lennon by tuning a guitar perfectly on the spot and launching into renditions of Little Richard and Eddie Cochran numbers from memory.Lennon recognized in McCartney a kindred spirit, someone with sharp musical instincts and an equally deep well of ambition. The young men bonded over a shared love for American acts like Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, and the Everly Brothers, and both carried the shared wound of losing their mothers at a young age. In their earliest writing sessions, they would sit in McCartney’s living room or Lennon’s aunt’s front parlor, trading lines and chord changes in what they later called an “eyeball to eyeball” style—a collaboration that became the foundation of their creative process.

Early in 1958, McCartney introduced Lennon to his fourteen-year-old friend George Harrison. Lennon was reluctant to bring in someone so young, but Harrison’s quiet confidence and guitar chops changed his mind. The clincher came one night on the top deck of a Liverpool bus, when Harrison played a note-perfect version of Bill Justis’s “Raunchy.” His technical skill won Lennon over, and with Harrison on lead guitar, the group’s sound gained a new precision and bite.

This early version of the band, still called the Quarrymen, modeled themselves on icons like Elvis Presley and Little Richard, but none shaped their early sound more than Buddy Holly and the Crickets. Holly’s clean harmonies, melodic songwriting, and two-guitar-and-bass setup became a model they would emulate. Their first known recording, made in 1958 under the name the Quarrymen, included a cover of Holly’s “That’ll Be the Day” and an original song called “In Spite of All the Danger.” It was an early glimpse of the style that would one day captivate the globe.

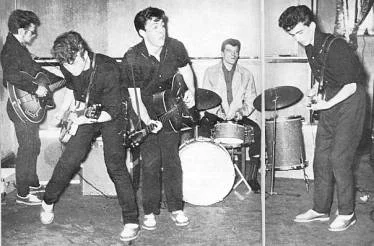

By 1960, the group had expanded to include Lennon’s art school friend Stuart Sutcliffe on bass and Pete Best on drums, joining Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison on guitars and vocals. They renamed themselves the Silver Beetles—an homage to the insect name of Buddy Holly’s Crickets—before Lennon suggested the sharper, more memorable “Beatles.” Under the guidance of their first informal manager, Liverpool club promoter Allan Williams, they secured a residency in the gritty red-light district of Hamburg, Germany. Performing at the Indra Club, they played exhausting, eight-hour marathon sets that pushed their musicianship and stamina to new heights. Here they learned to command a crowd, stretching their repertoire to include everything from Chuck Berry style rock and roll to show tunes, and driving their performances and sound into a raw, high-energy spectacle. It was during this formative Hamburg period that they adopted the mop-top haircuts introduced to them by their German friends, a look that would become one of their most enduring visual trademarks.

The group’s first stint in Hamburg came to an abrupt end in late 1960. George Harrison, then just seventeen, was deported back to England for being underage. Soon after, McCartney and Best were also forced to leave following an incident in which they set fire to their living space. Stuart Sutcliffe chose to remain in Hamburg with his German fiancée, while Lennon returned to Liverpool. With Sutcliffe gone, McCartney moved to bass, establishing the four-piece format of two guitars, bass, and drums that would carry them through their most celebrated years.

Back in Britain, the music scene still lagged behind the dynamic developments happening in the United States. Rock and roll was largely viewed as an American export, and British acts who tried their hand at it, such as Cliff Richard and the Shadows, were often seen abroad as mere imitators rather than innovators. The industry itself was dominated by four major companies—EMI, Decca, Philips, and Pye—and national radio airplay was tightly controlled by the BBC, which offered very little popular music programming. Most significantly, access to Black American rhythm and blues, the foundation of rock and roll, was scarce for British listeners and musicians, making it difficult for homegrown talent to fully tap into the genre’s roots.

Liverpool, however, was different. As a major port city with strong cultural and economic ties to the United States, it frequently received American records—especially rock and roll and rhythm and blues—before much of the rest of Britain. Sailors returning from America often brought back the latest records, which circulated informally among local fans and musicians. This meant that Liverpool’s youth had early exposure to a wide range of American artists, including Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Muddy Waters, and Ray Charles, often well before these musicians gained broader recognition in the UK. This unique access helped foster a thriving and distinctive musical culture in Liverpool that would play a crucial role in shaping British popular music.

A major influence on Liverpool’s grassroots music scene was the skiffle craze of the 1950s. Skiffle blended elements of folk, country blues, and traditional jazz, and was typically played on simple, homemade instruments such as washboards, tea-chest basses, and acoustic guitars. British youth discovered skiffle largely through American recordings and visiting Black musicians who brought these styles to the UK. The genre’s simplicity, based on three-chord progressions and repetitive verse forms with improvised accompaniment, made it easy for young players to form bands quickly and learn through hands-on experience. For many Liverpool musicians, skiffle provided both a technical foundation and a collaborative spirit that carried over into more complex genres like rock and roll. Because it required minimal training and inexpensive instruments, skiffle became a gateway for thousands of aspiring musicians, including those who would later form the Beatles.

By the early 1960s, the Liverpool scene had evolved into a full-fledged movement. Known as Merseybeat (named after the Mersey River that runs through Liverpool), this genre blended American rock and roll with elements of British folk and pop traditions. This style fused skiffle’s rhythmic energy with the tight harmonies, call-and-response vocals, and syncopated backbeats of early rock and rhythm and blues. Other Liverpool bands like Gerry and the Pacemakers and The Searchers helped define the Merseybeat sound, emphasizing upbeat tempos, jangly guitars, and vocal harmonies. Merseybeat provided the model for what a British rock band could look and sound like, laying the groundwork for the British Invasion of the American charts in the mid-1960s.

This music scene thrived in the youth clubs, dance halls, and expanding network of live venues clustered especially along Matthew Street in central Liverpool. The Cavern Club, which opened in 1957 originally as a jazz venue, quickly emerged as the heart of the city’s burgeoning rock and roll scene. By the early 1960s, it had transformed into a popular gathering place for teenagers and young adults, offering afternoon and evening sessions that catered specifically to Liverpool’s underage patronage. For local groups like the Beatles, the club provided a reliable and supportive platform to develop their stagecraft, experiment with repertoire, and build loyal fanbases from the ground up.

The band’s gritty, infectious sets soon caught the attention of Brian Epstein, manager of his family’s NEMS music store. Epstein first heard about the Beatles when customers repeatedly asked for a record that did not yet exist. Curious, he attended a lunchtime Cavern show in November 1961. What he witnessed was raw and unpolished but undeniably electrifying and he sensed enormous potential. Within weeks he offered to become their manager, despite having no prior experience in artist management.

Epstein’s had a swift influence on the Beatles. Drawing on his background in retail, theater, and high society, he helped refine their public image and introduce a level of discipline and professionalism that matched their musical ambitions. Out went the black leather jackets and rowdy stage antics; in came sharp matching suits, coordinated bowing, and curated setlists. He encouraged them to rehearse diligently and structure their performances more deliberately. As Pete Best later recalled, "He forced us to work out a proper program for the evening, playing our best numbers, not just the ones we felt like playing at the moment."

Beyond style and stagecraft, Epstein was a tireless advocate. He firmly believed the Beatles were destined for greatness and worked relentlessly to secure them a recording contract with a major label. He shopped them to record labels to no success until George Martin at EMI’s Parlophone agreed to a test session in 1962. Martin liked their harmonies and songwriting but doubted Pete Best’s drumming. The band—already frustrated with Best—made the change to Ringo Starr in August 1962, locking in the lineup that would define their career.

Their debut single, “Love Me Do,” released in October 1962, reached No. 17 in the UK—hardly a smash hit, but enough to break the surface and make some waves. With Epstein’s business savvy, Martin’s musical guidance, and Lennon-McCartney’s songwriting starting to blossom, the creative engine was fully assembled. By year’s end, the core elements of the “Fab Four” were in place: Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, Starr, with Epstein and Martin steering the ship.